By Wolf Richter

Resting Happily on Smoldering Powder Keg.

There is nothing like a big shot of leverage to fire up the stock market. And that’s what the market got in 2017, when the S&P 500 surged 26%, and in January 2018, when the index soared another 7.5% through January 26 – until suddenly something happened.

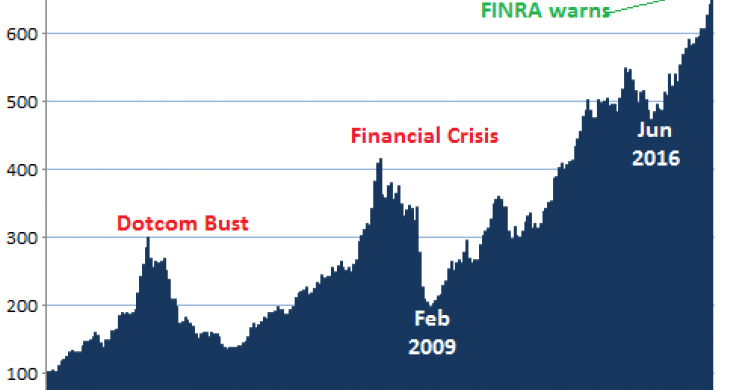

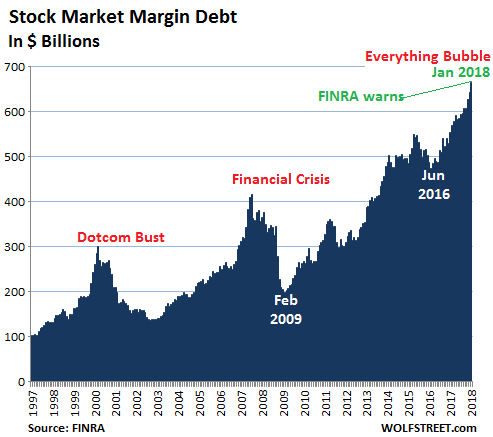

One measure of leverage in the stock market is margin debt – the amount individual and institutional investors borrow from their brokers against their portfolios – which surged $22.9 billion in January to a new record of $665.7 billion, according to FINRA (Financial Industry Regulatory Authority), which regulates member brokerage firms and exchange markets, and which has taken over margin-debt reporting from the NYSE.

For the 12-month period through January, margin debt soared $112.2 billion, among the largest 12-month gains in the history of the data series, behind only the 12-month periods ending in:

- December 2013 ($123 billion)

- July 2007 ($160 billion)

- March 2000 ($133.7 billion)

- November 1997 ($132 billion).

But it’s not just the recent surge; it’s the length of the surge. With only a few noticeable down periods, margin debt has soared for nine years in a row and now exceeds the prior peak of July 2007 ($416 billion) by 60%.

By comparison, over the same period, nominal GDP (not adjusted for inflation) has grown 32%, and the Consumer Price Index has grown 20%. In other words, margin debt has ballooned twice as fast from peak to peak as GDP and three times as fast as the Consumer Price Index.

The chart below shows margin debt based on the FINRA data, which includes margin debt from its own member firms and from NYSE Member firms, and is therefore more complete and larger than the NYSE data was. For example, NYSE margin debt in November 2017, the last month available, was $580.9 billion while FINRA’s data for November showed margin debt of $627.4 billion.

And in January, FINRA warned about the levels of margin debt – marked in green on the chart. Note the spike that started in June 2016:

Rising margin debt creates liquidity out of nothing, and this new liquidity is used to buy more stocks. When stocks are dumped to pay down margin debt, often in a bout of forced selling, the money from those stock sales doesn’t go into other stocks or another asset class. It just evaporates.

Stock market leverage, such as margin debt, is the great accelerator for stocks — on the way up and on the way down. It’s thrilling for investors on the way up, and treacherous for the market on the way down.

Margin debt is so out of whack apparently that even FINRA – which “self-regulates” the very entities for which lending against securities is an important profit center – issued an alert on January 18. It was “concerned,” it said, “that many investors may underestimate the risks of trading on margin and misunderstand the operation of, and reason for, margin calls.” It added:

Investors who cannot satisfy margin calls can have large portions of their accounts liquidated under unfavorable market conditions. These liquidations can create substantial losses for investors.

And it listed these specific risks:

- Your firm can force the sale of securities in your accounts to meet a margin call.

- Your firm can sell your securities without contacting you.

- You are not entitled to choose which securities or other assets in your accounts are sold.

- Your firm can increase its margin requirements at any time and is not required to provide you with advance notice.

- You are not entitled to an extension of time on a margin call.

- You can lose more money than you deposit in a margin account.

FINRA issued this alert before the recent sell-off. Just how volatile a highly leveraged market can get was amply demonstrated days later when the Dow dropped over 1,000 points a day, on two days, and the S&P 500 index dropped over 10% in five trading days. This sell-off was barely big enough to be visible on a long-term chart. It was just a reminder of what a highly leveraged market can accomplish in no time. But hey, stocks surged since, and nothing is going to happen to that smoldering powder keg.

Warren Buffett only made one large deal in 2017. And this is why his “recent drought of acquisitions,” as he says, is likely to continue. Read… Why Buffett Pulled Back: Companies Overvalued after “Purchasing Frenzy” Fueled by “Cheap Debt”

Read more by MarketSlant Editor