Source: Proven and Probable for Streetwise Reports 08/06/2018

Trey Reik, senior portfolio manager with Sprott USA, speaks with Maurice Jackson of Proven and Probable about the Fed's recent actions and what effect they are having on the gold and other markets.

Maurice Jackson: Welcome to Proven and Probable. I'm your host Maurice Jackson. Joining us for a conversation is Trey Reik, senior portfolio manager with Sprott USA.

We're delighted to have you here today to discuss the Federal Reserve's impact on peripheral markets. Mr. Reik, the Fed is in the process of implementing a dual policy of rate hikes and balance sheet reduction, which appear to have a duplicitous effect on peripheral markets. What are your thoughts on this dual policy and what can we expect from Chairman Jerome Powell during his tenure?

Trey Reik: Do I have about two hours to answer that question? I'm just kidding. There's a lot of information there. I think that Mr. Powell is obviously very capable of monetary stewardship with an enormous amount of experience and great judgment, and I think he will do a great job. He's got some difficult parameters to deal with. There is a little bit of a similarity to when Alan Greenspan first took over his Fed stewardship in 1987; he actually ascended to the position in August and tried to show the world that the Fed was on the case and under control, and people may forget but about a month later on consecutive days, the Fed actually raised the Fed funds rate on 25 basis points on two consecutive days.

We had had a big backup in ten-year yields and the S&P had been doing extremely well and all things looked to be in really good shape, and, of course, we had the fall of 1987 very soon thereafter. We have a lot of similarities and so far as Mr. Powell has just taken over and the market has a tendency to test a new chairman, we've had this backup in ten-year yields and the S&P's doing well. We have a chairman who seems to be focused on showing the market that he is control and so we've had these rate increases, so a lot of similarities there to ponder.

As we have written in past communications that the history of Mr. Powell's public statements and now that the extended transcripts from a lot of these meetings are coming out, Mr. Powell since he ascended to the Fed has been a fairly reliable critic of QE programs especially towards the QE3 stage. He ended up voting for QE3 as a Fed governor and permanent voter because that vote came up in his freshman year and generally freshmen don't rock the boat too much, but his public statements and the ones that are coming out from these extended transcripts demonstrate he argued fairly vehemently against the benefit of QE3 asset purchase along his line of reasoning that the market would always expect more and that the Fed was starting to encourage risk-taking and the search for yield, etc.

Now that he has become the Fed chairman and we have these large amounts of debt outstanding, I really do believe that he will go as far as he possibly can along the telegraphed lines of the scheduled balance sheet reduction. The Fed announced last September that it would roll about $10 billion per month off the balance sheet in Q4 of 2017 and then that would increase by $10 billion per month each quarter thereafter, meaning the monthly total in Q1 would be $20 billion and the monthly total in Q2 would be $30 billion, $40 billion in the third quarter, and then theoretically by the end of this year, in the fourth quarter, $50 billion per month.

The $50 billion per month times three is about $150 billion per quarter or a run rate of $600 billion. Ben Bernanke was fond of saying that every $200 billion or so of QE was equivalent to about a 25 basis points rate cut when it was QE. One would assume that in reverse that equates to something on the order of about 25 basis points. Each $200 billion of rolling assets off the Fed balance sheet should equate to something like a 25 basis points rate hike.

If we are at a $600 billion annual run rate and balance sheet deduction by the end of the year, that would mean that there's 75 basis points of tightening just from the balance sheet reduction. I think everybody by now is fairly aware that the Fed's dot plot on average predicts about four rate cuts in the current year and plying two more for the balance of 2018 and another three or four next year, and believe it or not, another one or two in 2020. That's the telegraphed policy and, as I mentioned, I think Chairman Powell, given that he didn't support a lot of asset purchases originally, I think he will be as dedicated as possible to try to follow those policies.

Maurice Jackson: Let's discuss how the Fed is or will have an impact on the peripheral markets beginning with emerging markets, which I like to term as third world economies. Does the Fed fundamentally grasp the dynamics of the situation?

Trey Reik: Interestingly there was an IMF conference that was hosted in Switzerland a couple of months back at which Chairman Powell was invited to speak on the topic of the impact of Fed policy on other countries and how they can control their own fiscal economies in the environment of Fed monetary decisions. In other words can emerging markets and other countries still run their own fiscal policy when the Fed is involved in changing its monetary policies? It gets to the Triffin dilemma, etc., in terms of whether any country can issue the reserve currency for the world because it sets up a situation where internal demand per dollars is not always in sync with external demand for those dollars.

At this conference Mr. Powell raised a few eyebrows in the assertion that monetary policy of the Fed and its impact on the rest of the world is vastly overrated. I think having watched that tape it's interesting. It's on the Swiss national bank website. I would encourage everyone to take a peek because I've noticed discernible facial expressions of surprise by the other folks on that panel because quite frankly, Mr. Powell made a few statements that we felt were fairly wild claims in terms of the lack of impact of what the Fed has done recently on global monetary affairs.

What Mr. Powell is playing out is that since the late 1990s when emerging markets had one brand of challenges, such as being linked to the dollar and not having sufficient foreign exchange reserves, there have been changes and improvements on the governmental level in a lot of emerging markets in relaxing those pegs to the U.S. dollar and building up FX reserves to deal with currency pressures. But what this ignores is that outstanding debt in emerging markets has roughly quadrupled over the past decade, from about $5 trillion to $20 trillion.

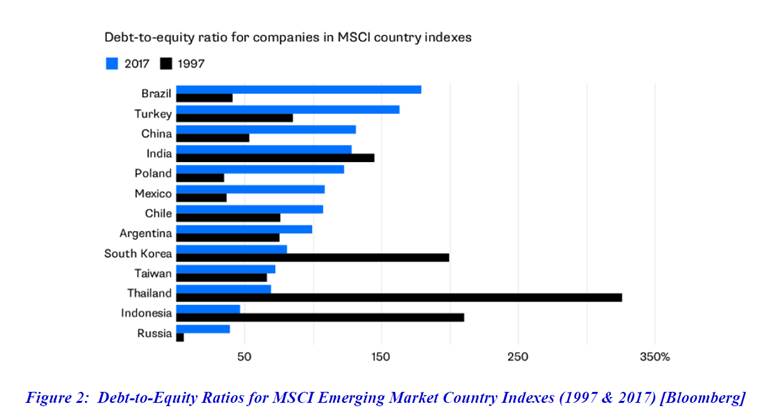

While there have been some improvements on the governmental level, the actual dollar-denominated debts that are outstanding have continued to spiral upwards. Some of the things that Mr. Powell is stating as positive developments are more academic in nature. If we look at the percentage of debt to equity ratios for corporations in the MSI country indexes, the average is way above where it was in the late 1990s.

It's more broadly based, so Brazil, Turkey, China, India, Poland, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, South Korea, Taiwan. These are all environments or economies that have had an enormous increase in that outstanding debt. The dollar-denominated portion of that has recently been estimated by the BIS to be, believe it or not, $11.4 trillion. If we have $11.4 trillion of dollar-denominated debt overseas, about $3.7 trillion of that by the way in emerging markets, it is a mathematical certainty that when the Fed starts to tighten there is going to be direct deleterious effects on the economies of emerging markets.

I think the highest dollar-denominated debt to GDP economies are Chile, 33%; Turkey is about 22%; Mexico is 22%. Not an important trading partner is Argentina, about 20%. In those countries, Mr. Powell can say anything he wants or claim whatever he wishes, but as the Fed tightens liquidity for dollar funding around the globe, there's going to be pronounced pressure in those countries and I think we're starting to see that in recent months.

Maurice Jackson: Let's shift here to global financial institutions. My first thoughts are bailouts and derivatives. What concerns do you see here and what type of response can we expect from the Fed?

Trey Reik: It's interesting. The global financial institution issue with respect to Fed tightening has clearly been largely limited to the plight of Deutsche Bank. What's going on with Deutsche Bank right now is really very different than what's going on with any other global institution and obviously there are some unique mismanagement issues at Deutsche Bank so I think that most investors who don't own Deutsche Bank shares are prone to say, "Well, I don't own it so it doesn't affect me." It hasn't spread to other global financial institutions.

What is funny about that is even though you may not own shares of Deutsche Bank, that isn't going to help if Deutsche Bank further hits the skid because Deutsche Bank has a $157 trillion CDS book, which is two times global GDP, so whether you own the shares outright or not, everything that you do own is certainly going be affected by the status of that derivative book. That's just the CDS part of their derivative book.

The other thing that's interesting is if you broaden this analysis to what the Basel-based Financial Stability Board terms as systemically important banks, which is a fairly widely used term. The percentage of systemically important banks trading more than 20% below the recent peaks, which in essence placing them in a bear market, included 41% of the total, which include entities like the Agricultural Bank of China and Mitsubishi Bank of China, Credit Suisse, Prudential. The list is lengthening rapidly and once again, there's a bit of cognitive dissonance to assume that these types of dollar liquidity pressures aren't spreading because they are.

Maurice Jackson: Let's make the conversation here more U.S. centric, focusing on U.S. corporate credits. There's this sophism that corporate balance sheets are in great shape. Let's focus here on companies just listed on the S&P 500. How accurate is this statement?

Trey Reik: That's a great question. We are all aware vaguely of a thinning in market ranks. We happen to be talking in the middle of the FAANG reporting season and Apple is doing well and Amazon is doing well. Facebook not so much. We really have narrowed the focus on these massive companies that quite frankly do have a lot of cash.

There is this conclusion that all companies are in great shape. You ask to focus on the S&P itself. Corporate cash balances entirely in the United States measured according to the Fed's Q1 Z1 reported about $2.66 trillion and that is in fact a new all-time high, but total corporate debt also is hitting new all-time highs at $9 trillion. If we take the $2.66 trillion and we subtract the $9 trillion, actually corporate cash net of debt registered in the first quarter, once again, this is according to the Fed, not according to me. Hit an all-time low of negative $6.4 trillion.

That's a pretty simple equation. Just corporate cash, which everybody is focused on, $2.6 trillion minus total debt and the first quarter of this year registered a new all-time low of negative $6.4 trillion. When you narrow in on the S&P, the 500 S&P corporations have $1.9 trillion of that $2.66 trillion total that the Fed measures. If we look at who owns that $1.9 trillion, the top 25 companies in the S&P hold 56% of it and the top 50 hold 68% of it.

That's 50 of 500 of 70% of the cash and the bottom 250 hold next to no cash on the grand scheme of things. The cash is concentrated in a very small group of companies, which of course are the ones that everybody spends most of the time on in this FAANG-type environment that we're living in the last several quarters. What people aren't focusing on is there's about a $1.5 trillion corporate debt rated junk and another $3 trillion rated one rung above. Not to mention about $1 trillion in lever loans, which we're getting back to almost no covenant protection.

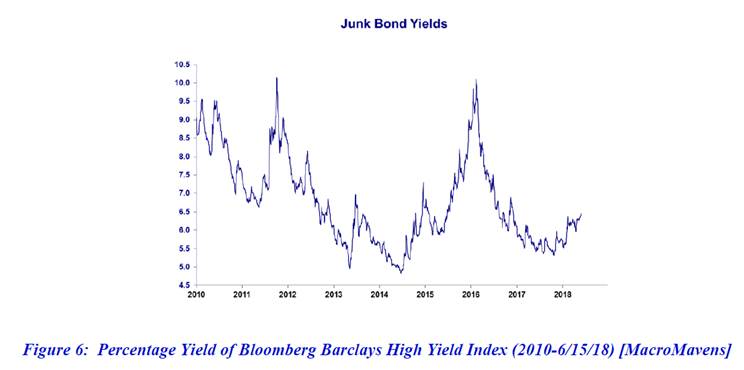

We are about $5.5 trillion of hot potato debt, which stands directly exposed to any deterioration in corporate credit trends. Of course, we haven't seen a huge surge yet in defaults but if you look at junk bond yields and any other sort of sensitive measure those are starting to hook back up pretty rapidly.

Maurice Jackson: Hearing you discuss the number of issuers in the S&P 500 that actually holds cash reminds me of Pareto's Law, which also ties in to my next question for you, which is U.S. consumer credits, does the automobile sector remind you of subprime?

Trey Reik: The automobile renaissance or at least the renaissance in sales and revenues and earnings of the past three years, I think this is fairly well documented to have been based on extending the lengths of loans and reaching further down the credit scale for borrowers. Larger and larger portions of auto loans are now seven years long, believe it or not, which is an amazing fact because obviously no matter what rate you're borrowing at or advertising after seven years, you're going to have a lot of upside down vehicles.

The trend in the most recent two years has been to take that negative equity in cars that are being traded in both the used car and the new car market. I don't have the numbers right in front of me. I think it's fair to say that somewhere in the 30%, 40% range of all new car purchases where there is a loan involved in the trade in are underwater and that equity is being tacked on to the new loan. Obviously when you had rates that were 0'ish percent, that type of behavior, while I think it's fairly reckless, is doable because frankly the payments remain low, but now that we're ratcheting up Fed funds from 0% to 2%, that's a really big difference, a big delta in this type of strategy being workable.

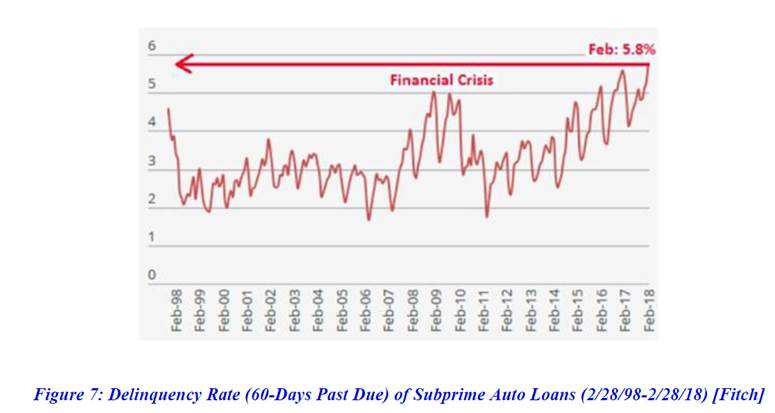

A lot of this credit has stopped being created and if you look at any of these subprime classes in the past two or three years, they haven't really matured. These credit pools haven't had a long time to mature but they're already facing default rates far higher than at the peak of financial crisis. Total auto credit is roughly $1–$2 trillion, obviously much less than the $10 trillion in total mortgage credit at the peak of the real estate boom into 2007–2008 period, so it's about a tenth as large and a lot of the bad credit is centered in even smaller areas of that total trillion-dollar pool.

This brings up another observation, which I think Stephanie Pomboy at MacroMavens first taught me, and that is that a lot of people take solace in the fact that debt service ratios remain low. Broadly speaking, the Fed's debt service ratios take disposable income and aggregate that and then they take the debt service required for revolving credit and car loans and different measures, even taking into account apartment, rent, leases, all these things.

We take debt service ratios aggregately and we look at disposable income and the ratio is very low. In fact, it's near historic lows because, A, there has been some growth in income and B, rates are very, very low. That problem with that is looking at the intersection of aggregate disposable income and aggregate debt service speaks to precisely no one because one group of Americans has most of the debt and the debt service obligations, and a fairly mutually exclusive group of Americans has most of the income, and they're not the same. Your stress levels of things like subprime auto loans, etc., are going to be much faster and much worse than anything that will ever be telegraphed by looking at things like the aggregate debt service ratios. I think that's really an important point.

Maurice Jackson: A correlation I see 10, 15 years ago, I was buying real estate and there was no income verification. I'm starting to see that now with auto loans; it's the same process that they were using 10, 15 years ago. It seems like we don't learn. History repeats itself and that's something I don't ever hear really mentioned. Again, I want to restate that here for our audience is you're actually now able to get loans, auto loans in particular, with just stating your income without verifying that you actually have the income there. That's really one of the reasons why we had that catastrophic bubble 10 years ago.

Trey Reik: Our anecdotal evidence suggests that's all hitting a wall. In other words the loose auto terms and in amount percent of autos that are going out in lease-type of arrangements. That's really plummeting because leasing again works really, really well in a low interest rate environment because the cost of money is really the only cost and it's that cheap. You can put cars out for lease at really, really attractive rates.

That's really hit a wall as well, and I think there's certainly a lot of evidence that the leasing pools that are coming due this year and next year are going to really take a hit at bank earnings because the used car market is very soft. I think the whole auto thing is literally hitting the wall this year.

Maurice Jackson: Regarding credit card debt, what can you share with us about U.S. personal interest payments?

Trey Reik: I think that people forget how quickly rising credit card interest rates affect consumer solvency here in the United States, so when the Fed starts to raise rates, sometimes we look at the Fed's funds rate as something that once again doesn't really affect us but it has had obviously an immediate impact on the interest rates charged by credit card companies, which are now up around 15.5% and there are very, very strong correlations between increasing this rate and personal interest payments.

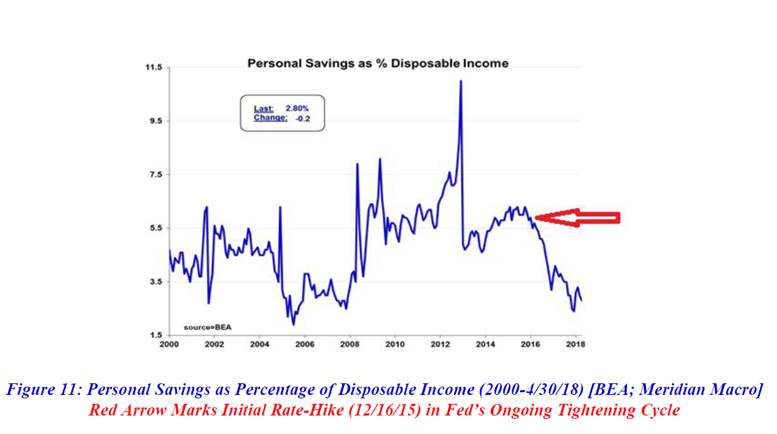

There's an immediate connection to delinquencies of revolving credit. Once again, it's the peripheral type stuff that gets hit first. For example, the 60-day delinquency rate of subprime auto loans of all lenders in February this year hit 5.8%, significantly above the financial crisis peak, which was right around 5%. Personal interest payments non-mortgage are already at new all-time highs. I've even noticed and I put forth a fairly strong correlation to when the Fed started raising interest rates and what's happened with the personal savings rate, which has collapsed in the past six months.

As these rate hikes start to take hold, and things like rising interest rates charged on credit cards, it puts a severe cramp on the peripheral credit scores of a U.S. consumer and I think you've already seen that in a lot of different spots. For Chairman Powell to continue to increase the Fed's fund rate, he is going to have to endure knowledge of the fact that he is causing an enormous amount of stress in the more challenged portions of the U.S. consumer population.

Maurice Jackson: It would be interesting to see how that comes to fruition in what his response will actually be. I'd be remiss if I didn't ask you this, but how will tariffs and a trade war affect the Fed and the peripherals? Can you provide us with an example?

Trey Reik: That is the most frequent question I have been receiving lately, "Why isn't gold doing better?" Because keep in mind that's what I focus on most of the time but there's been this dispute that given the fact that tariffs are bad, that gold should be doing better. I think that frequently with gold at least, people have a tendency to fall into knee-jerk reasoning and while it is true that tariffs are bad for global GDP and potentially inflation area in the long run, the immediate impact of tariffs at least in this iteration has been commodities have really gotten walloped.

Really beginning June 1 with the imposition of the steel and aluminum tariffs by the Trump administration, a commodity complex started to underperform dramatically and then I believe it was on July 10th in the evening when the Trump administration announced its plans for another $200 billion worth of Chinese goods to have 10% tariffs, which in the last 48 hours, President Trump seems to be telegraphing a willingness to put 25% tariffs on those $200 billion worth of goods. The commodity complex has really rolled right off the map on the 11th of July, the morning after the announcement of those $200 billion in incremental 10% tariffs.

That was the worst day for the Bloomberg commodity index since 2014. Gold is involved on almost every commodity index. In fact, it's the largest single component of the Bloomberg commodity index at 9.2%. There is a tractor beam pull on gold when the commodity complex is performing as poorly as it has. On that day, the 11th after the evening of the 10th announcement, the average metal in the Bloomberg commodity index zinc, etc., was down. Copper was down in excess of 3%. Oil was down five. On that day gold was down 1.09%.

One could make the case that gold in fact is acting as a store of value precisely as it should by being a little bit less volatile than some of the other commodity components. The way that a lot of this can work back to affect the general markets a lot quicker than people realize. A good example would be that in President Trump's efforts to show he can and will be tough on Russia, there were a group of tariffs introduced on certain Russian oligarchs back in April.

The firm that took the biggest brunt of the sanctions that were announced in early April were on Rusal and its leader, Oleg Deripaska, who's a close Putin ally. Rusal happens to be the world's largest aluminum producer with about a 7% global market share, and I'm sure that President Trump's advisers pointed out that this would be a good company to target because by taking 7% of global aluminum out of dollar-denominated markets, that would be a double-whammy to help the impact on domestic producers of aluminum and steel in concert with the tariffs that he already imposed.

Rusal was chosen. I'm not going into all the details but bonds promptly went no bid and the equity in Rusal Hong Kong listed shares collapsed about 72% in a period of a few weeks. This is an event that clearly didn't get on the radar screen of most domestic investors who are going home every day excited about Google and Amazon's new heights. However, Mr. Putin seemed to take offense to the fact that one of Russia's most important corporations and one of his close friends was being targeted, and it turns out that we know that in April Russia sold a little over half its total treasury holding, $47.5 billion in the month, and we now know that most of the rest of the holding was sold the next month in May.

Russia pretty much liquidated $100 million worth of treasuries in a two-month period in April. Of course that was the first time the ten-year yield poked its head above the 3% barrier since December of 2013, and it's just interesting that in retrospect that 35 basis point jump in ten-year treasury yields in April may have had as much to do with perhaps some ill-advised measures, because the Treasury Department is certainly in the process of reconsidering how draconian it wants the result sanctions to be, but it's certainly possible that the resulting sanctions had as much to do with that eye-popping jump in ten-year treasury yields as expectations for economic growth or inflation. We're definitely getting to the point where some of these peripheral events are starting to have blowback to very large and important asset classes.

Maurice Jackson: If I'm not mistaken, Russia, when it dumped those treasuries, did it not go out into the market and share that it was going to purchase gold?

Trey Reik: There were some stories that pointed out that the reduction in the treasury holdings, especially the $47.5 billion a month in comparison to Russia's gold holding, made gold a larger portion of foreign exchange reserves than treasuries. The reason I don't focus on that too much is that anyone who has followed Russia closely is aware of the fact that Russia has methodically and meticulously added to its gold reserves pretty much every month for the last, oh gosh, 10 years and certainly in the last three years. I just read a story this week that Russian gold holdings are starting to rival Soviet era holdings in gold.

It's such a methodical increase in its gold holdings. I think it's a little unfair to say what that $47.5 billion went to purchase gold. The portion that Russia has been directing towards gold accumulation each month remained roughly the same. It's just that the accumulative total of the amount of gold on the Russian Central Bank balance sheet exceeded the treasury total for the first time in a very long time because of the big decline in treasury holdings. Where did the rest of the $47.5 billion go? My guess is that it went into a Russian version of QE to stabilize bonds of not only Rusal but some of the big Russian banks that render a lot of pressure as well with the threat that their results are going to be locked.

Anyone who did business with Rusal and U.S. dollars was going to be sanctioned so that put a lot of pressure on the banks too, and I would bet the lion's share of that $47.5 billion went to a Russian version of QE. The Fed printed money and directed it at a very toxic amounts of Bear Stearns, etc., balance sheets in our first example of QE.

First of all, we have the advantage of being able to print dollars when we buy toxic assets for the Bear Stearns balance sheet; Russia obviously doesn't have the latitude to print dollars so it had to find them to buy and stabilize dollar-denominated obligations of these banks.

Keep in mind aluminum is priced in dollars, so there was an order book before it was sold but all of a sudden was threatening in terms of where dollars were going to come from. Russia had to find the dollars somewhere and very clearly the treasury holdings were the biggest pile of dollars. I believe that's why they were liquidated and I think the proceeds went to stabilize the dollar-denominated obligations of banks and Rusal itself.

Maurice Jackson: Trey, what keeps you up at night that we don't know about?

Trey Reik: Boy, asking a gold guy that question, you're likely to get a tidal wave. I really think that the biggest thing that is being missed by consensus and by markets and by the financial media is the amazing degree of inflation that the Fed has miraculously been able to foster in financial assets at least to date without causing CPI-type inflation. I will go to my grave really never understanding how the Fed has been so successful in channeling inflation; keep in mind QE is deliberately designed to inflate the prices of treasuries and MBS and bring those rates down.

That was the intention of the programs so when folks say that QE didn't cause any inflation, they're looking in the wrong place because it was designed to inflate financial asset prices and it was remarkably successful. I think when stocks reach highs of the past two to three years a common refrain or explanation is that expanded valuations are rational because of why? Because we have low rates. Now that the Fed is raising rates and on the long end, we seem to be flirting with the breakout of this 35-year down channel, as you know equity investors are nothing if not flexible and so for several years they would cite low interest rates as the reason to justify premium valuations.

Now that rates are rising, the common refrain is usually, well, it won't matter that much. At some point, both the short end for what the Fed is doing and at the long end of what the ten year has been doing, this is going to have probably in a very short period of time a big impact on financial asset prices. The measure that we look at which really is an eye-popping measure is the Fed's own measure of household net worth.

In the Z1 report, which comes out quarterly, one of the things that the Fed measures is household net worth and it usually gets mentioned with GDP and total debt household net worth. If we look at the first quarter of 2009, household net worth was at $54.5 trillion and GDP was at $14.1 trillion. If we fast forward nine years to the first quarter of 2018, GDP had increased $6 trillion from $14 to $20 trillion and household net worth had increased $46 trillion from 54 to a little over $100 trillion, 500% of GDP for the first time in the history of the United States.

What that means is that for the past nine years, household net worth or wealth, if you will, in the United States has been increasing eight times faster than output for GDP. There's a lot of things that I don't know or can't predict but one thing I know for certain is you can't keep increasing wealth eight times faster than output in any society forever.

I think that household net worth number, which is really stocks and bonds and real estate, is a number to really focus on because the increase in short-term rates and flirting with this 3% level on the ten year, they are going to have a very, very out-sized impact on this incredible generation of household net worth or inflated prices of financial asset prices. I really think it will surprise people how quickly those levels can adjust on the downside.

Maurice Jackson: It's already surprising to hear that right now.

Trey Reik: How does gold fit into that just as a last footnote? Well, when financial assets are falling, obviously that's a time that gold is a good store of value or people desire to get a little money out of the financial system. When that starts to happen, the Fed, as it did with QE1, QE2, Operation Twist, QE3, is very likely to respond maybe not with a QE decision but with some policy, as it says sometimes it's the medicine and not the disease; that will be very gold bullish as well.

Both in terms of downward reevaluation of enthusiasm for U.S. financial assets and the result and rationalization of debt that that will entail having something that can't default or be the base like gold outside the financial system will all of a sudden look a lot more palatable than it may today.

Maurice Jackson: What did I forget to ask?

Trey Reik: Well, we didn't focus as much on gold as I think sometimes you and I like to chat about. The question in my mind quite frankly is with gold here at $1225 (U.S. Currency), what is going to change between now and the end of the year that has the potential to put a little bit more spunk back in gold markets? I think the answer is recognition that the Fed is going to change its telegraphed balance sheet policy in terms of that scheduled uptick in balance sheet reduction $10 billion per month.

It's one thing for me to cite credit stress and peripheral stress and emerging markets, but it's very different when the Fed starts to send signals that it's concerned about the impacts of its dual policy objectives as well, and at the June FOMC, the Fed increased the rate or the pays on excess commercial reserves. It's commonly referred to as the IOER, which is essentially the excess reserve interest rate. The Fed increased that only 20 basis points during an FOMC meeting when it increased Fed funds 25 basis points, which doesn't sound like much but the reason that it did that is there's already such a growing pressure for commercial banks to find and fund their reserves at the Fed.

Keep in mind when the Fed prints money and buys treasuries from Jamie Dimon and Lloyd Blankfein, that money stays on the Fed's balance sheet as excess commercial reserves and everybody is happy, but when we start reducing the Fed's balance sheet there is, believe it or not, an outsize effect about 1.5 on a decline in commercial banking reserves, which are required, and those don't grow on trees so we're starting to see commercial banks bid up the Fed funds rate, which is essentially the cost of reserves what they pay their Fed for borrowing money at a faster clip than the Fed intends them to do.

For example, the way the Fed controls the Fed funds rate these days is it has a target range. We used to have a specific rate and the Fed would intervene every day. Now, there's a target range, which is a 25 basis points spread, and the Fed likes the effective Fed funds rate to be right at the midpoint of the target range. A couple of times in early June, because of the pressure on commercial bank reserves on funding, the required reserves were increasing.

The U.S. commercial banks bid up Fed funds within five basis points of the top end of the Fed's targeted range. If Fed funds trade above the targeted range that the Fed sets, that is somewhere between an embarrassment and a credibility hit to the Fed. You can choose which way you want to look at it. It's certainly nothing less than an embarrassment and certainly as much as a credibility shot that the Fed really doesn't have control of Fed funds.

The Fed lowered, or introduced for the first time ever, a gap between the interest paid on the excess commercial reserves and the Fed fund itself to try to induce banks to compete less for that funding source for reserves. It sounds wonky. It is wonky but it's important because it demonstrates that the Fed is cognizant of the fact that by reducing its balance sheet, it is already impacting liquidity and in ways that it perhaps didn't perceive.

To me, it's pretty obvious that the Fed is not going get anywhere near the $2 trillion or so that people think that the balance sheet is heading towards and I've started to read things in recent weeks by noted economists who suggest the Fed may not get that balance sheet below $4 trillion before it abandons balance sheet reduction. Balance sheet reduction, by the way, to date since October is $179 billion. It'll be interesting to watch between now and the end of the year if the Fed is able to stay on track with that telegraphed balance sheet reduction.

That is the type of event that I think will start to sway consensus back to our view that it is not likely that rate increase and balance sheet reduction program that has been telegraphed is going to transpire as advertised. I think that will start to put a bid back in the gold market.

Maurice Jackson: These are certainly going to be some interesting times under of the tenure of Chairman Powell. Mr. Reik, tell us about your services at Sprott and please share the contact details.

Trey Reik: Sprott has, I would say without a doubt, the most investor friendly bullion vehicles in the marketplace, the Sprott physical bullion products, largely gold, but silver and platinum and palladium, have a redemption feature that permits investors to turn in their shares individually for the underlying metal. The other thing that's different about the Sprott bullion products is that they are eligible to U.S. investors for long-term capital gain tax treatment. Some of the competing and leading market leaders there do not have a redemption feature and are not eligible for long-term capital gain tax rates and instead are taxed that the 28% collectible rate for bullion and collectibles and coins.

I think that's a great way for anybody to get started with a bullion investment. We have some products at Sprott that are, I think, smarter ways to look at equity ETF opportunities in both the large and small cap arena. Then what I'm focused in on is the individually managed separate accounts of gold miners and we'd be interested in speaking with anyone about a separately managed, actively managed equity account if anyone has the interest. My email is treik@sprottusa.com. Anybody can give me a ring if they want to talk about gold equities generally or some companies in particular. My phone number is 203-656-2400.

Maurice Jackson: Please put in subject line, Proven and Probable. And last but not least, please visit our website, www.provenandprobable.com, where we interview the most respected names in the natural resource space. You may reach us at contact@provenandprobable.com.

Trey Reik of Sprott USA, thank you for joining us today on Proven and Probable.

Maurice Jackson is the founder of Proven and Probable, a site that aims to enrich its subscribers through education in precious metals and junior mining companies that will enrich the world.

Want to read more Gold Report articles like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you'll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent articles and interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Streetwise Interviews page.

Disclosure: 1) Statements and opinions expressed are the opinions of Trey Reik and Maurice Jackson and not of Streetwise Reports or its officers. They are wholly responsible for the validity of the statements. Streetwise Reports was not involved in the content preparation. Trey Reik and Maurice Jackson were not paid by Streetwise Reports LLC for this article. Streetwise Reports was not paid by the author to publish or syndicate this article. 2) This article does not constitute investment advice. Each reader is encouraged to consult with his or her individual financial professional and any action a reader takes as a result of information presented here is his or her own responsibility. By opening this page, each reader accepts and agrees to Streetwise Reports' terms of use and full legal disclaimer. This article is not a solicitation for investment. Streetwise Reports does not render general or specific investment advice and the information on Streetwise Reports should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Streetwise Reports does not endorse or recommend the business, products, services or securities of any company mentioned on Streetwise Reports. 3) From time to time, Streetwise Reports LLC and its directors, officers, employees or members of their families, as well as persons interviewed for articles and interviews on the site, may have a long or short position in securities mentioned. Directors, officers, employees or members of their immediate families are prohibited from making purchases and/or sales of those securities in the open market or otherwise from the time of the interview or the decision to write an article, until one week after the publication of the interview or article.

Proven and Probable LLC receives financial compensation from its sponsors. The compensation is used is to fund both sponsor-specific activities and general report activities, website, and general and administrative costs. Sponsor-specific activities may include aggregating content and publishing that content on the Proven and Probable website, creating and maintaining company landing pages, interviewing key management, posting a banner/billboard, and/or issuing press releases. The fees also cover the costs for Proven and Probable to publish sector-specific information on our site, and also to create content by interviewing experts in the sector. Monthly sponsorship fees range from $1,000 to $4,000 per month. Proven and Probable LLC does accept stock for payment of sponsorship fees. Sponsor pages may be considered advertising for the purposes of 18 U.S.C. 1734.

The Information presented in Proven and Probable is provided for educational and informational purposes only, without any express or implied warranty of any kind, including warranties of accuracy, completeness, or fitness for any particular purpose. The Information contained in or provided from or through this forum is not intended to be and does not constitute financial advice, investment advice, trading advice or any other advice. The Information on this forum and provided from or through this forum is general in nature and is not specific to you the User or anyone else. YOU SHOULD NOT MAKE ANY DECISION, FINANCIAL, INVESTMENTS, TRADING OR OTHERWISE, BASED ON ANY OF THE INFORMATION PRESENTED ON THIS FORUM WITHOUT UNDERTAKING INDEPENDENT DUE DILIGENCE AND CONSULTATION WITH A PROFESSIONAL BROKER OR COMPETENT FINANCIAL ADVISOR. You understand that you are using any and all Information available on or through this forum AT YOUR OWN RISK.

Image Sources: Sprott Institutional June 2018 Strategy Report.

Read more by MarketSlant Editor