Maybe Deep Dissatisfaction Has A Point

by Jeffrey P. Snider in Currencies, Economy, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, Markets Tags: they really don't know what they are doing

To complete a trifecta, maybe someone could interview Alan Greenspan about rational exuberance. The last of the latest Fed Chairmen, Janet Yellen, purports today that the next financial crisis will not be in “our lifetimes.” The issue, however, isn’t even crisis so much as credibility. Given that she and the rest of them had no idea about the last one until it was almost over, we might be forgiven for rejecting her thesis outright – and it having nothing at all to do with the current or expected future state of finance. She is nearly the last person that should be speaking on that topic.

The very last opinion that should be solicited would be from her immediate predecessor, Ben Bernanke. He was busy just yesterday doing what he does, meaning polishing up as best he can his legacy. Speaking on invitation to an ECB conference in Sintra, Portugal, the same where Mario Draghi caused his “reflation” stir, the former Federal Reserve head gave a speech he modestly titled When Growth Is Not Enough.

It is typical Bernanke, who has taken to these kinds of tricks in order to justify the apex of his career. For him it was a top; for the rest of the world not at all. The last thing anyone associates with Bernanke is growth. His speech would have more appropriately been called When Not Enough Growth.

During his tenure he was clearly bipartisan, or at least largely free of partisanship. In 2017, he is not. His general purpose in appearing was to acknowledge, like many economists are being forced to, the great dissatisfaction around the world with the results of largely his exertions. Before last year, economists could plausibly claim things were OK if not great, but after Brexit and especially Trump it is no longer possible to live that deep in denial.

It is to the current President that Bernanke clearly feels his reputation most threatened, describing yesterday the stunning political revolt as, “last November Americans elected president a candidate with a dystopian view of the economy.” In doing so, he betrays his own true motivations. Ben Bernanke’s legacy, even more so than Barack Obama’s, is Donald Trump.

In particular, Americans generally have little confidence in the ability of government, especially the federal government, to fairly represent their interests, let alone solve their problems. In a recent poll, only 20 percent of Americans said they trusted the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time”. The failure to prevent the global financial crisis did not help this situation of course, but these attitudes are long-standing, going back at least to the 1970s. [emphasis added]

The highlighted portion wasn’t some trivial footnote, a small matter among larger ones. It was everything, especially for the Federal Reserve who before the crisis declared that what Janet Yellen says right now. For an institution claiming to be the height of economic competence and authority, the Panic of 2008 was all that mattered.

But if that was the only fault with the so-called establishment elite, it would still be enough to register as it finally has with the public. The tragic comedy did not end there, however, and Bernanke knows it well. He asserts again in this latest speech something he referred to in a little-noticed blog post (for Brookings) from last October.

Economists Charles Jones and Peter Klenow had at that time published a paper the former Fed Chair immediately seized upon. They proposed that things like GDP or nation income figures weren’t comprehensive measures of social advance. Jones and Klenow created an “economic welfare” statistic that incorporated intangibles like vacation time, life expectancy, and inequality.

Bernanke is a very smart guy, but he isn’t as clever as he may think of himself. If you claim to be running an economy and it doesn’t produce in all the traditional ways of output and income, then suddenly saying those aren’t the appropriate standards is as transparent as it gets. It’s not quite convincing given his own public history to in 2017 try to say “it wasn’t all bad.” Methinks the money printer doth protest too much.

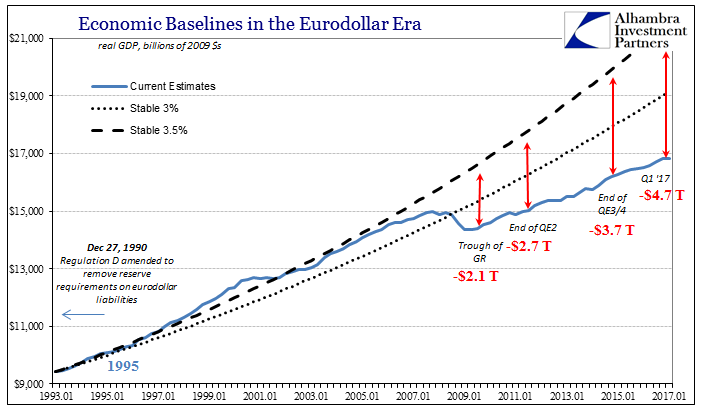

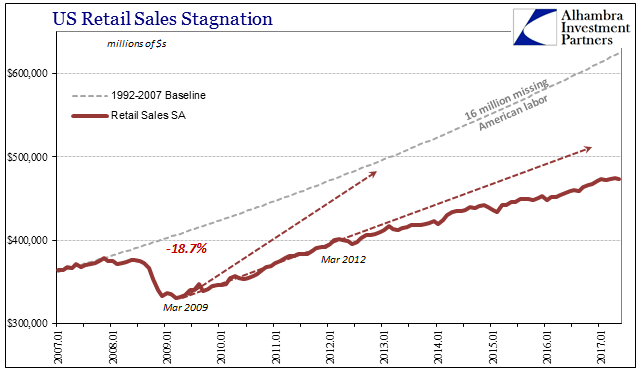

And that is really the point. Quantitative easing was designed and sold to the public as the right amount of the right program to get the economy back going again after what was a catastrophic error. To long after its conclusion suggest that maybe GDP or national income estimates aren’t good enough standards for measuring and then appropriately crafting a response is to totally undercut that thesis; it was the correlation with GDP that led to the Q part of QE. Moving the goalpost only proves that QE wasn’t what you thought it was.

If you have to refashion standards to suggest why you maybe could have possibly not performed so badly, then maybe you really did and maybe most people by now know it. And to further think along just those lines, perhaps the election of Trump isn’t so extreme as it might first seem to the delicate orthodox sensibilities of the perpetually slow and ignorant. Maybe it doesn’t leave us in economic dystopia, but that is at least the direction we might have been traveling all this time you called it a recovery.

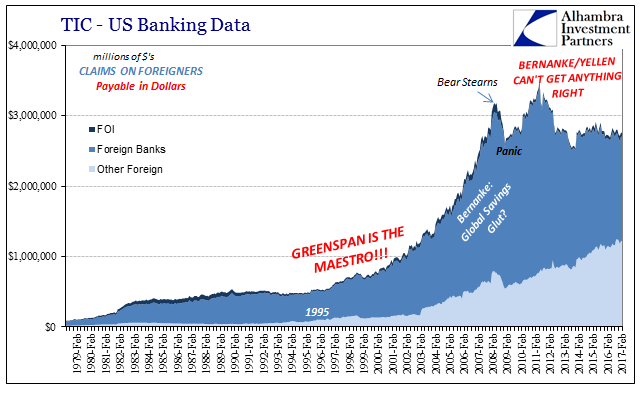

What’s even more illuminating is the lack of mention of the Great “Moderation.” It has been almost excised from official history. The period where central bankers created forever new plateaus of prosperity, winning monetary policymakers especially undying admiration and too frequently cultish status has been completely transformed into outright mistrust; so deep it has infected, as Bernanke’s speech concedes, all levels of government and establishment. Yellen is left nearly the undisputed anti-maestro. Only now do people like Bernanke admit there might be reasons.

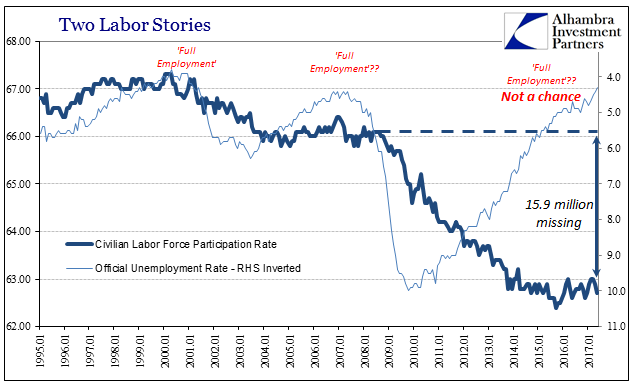

Bernanke once said (2004) that the Great “Moderation” was indeed the work of monetary policy, so its years later omission is all the more telling. At least then economic pronouncements matched outward economic conditions. No one was compelled to challenge the unemployment rate, or recognize the mainstream clinging to it was out of clear and growing desperation rather than scientific analysis. They really didn’t know what they were doing, and now they worry too many people might have figured that out.

It is another small (emphasis on small) step in the right direction. Economists like Bernanke are feeling very uncomfortable, as they should. They have much to answer for and for the first time in ten years are feeling enough pressure to start doing so. That the first round leads them to different but still nonsense is to be expected. As I wrote above, they aren’t as clever as they might think, and you not as dumb as they believe – or used to.

Read more by MarketSlant Editor