Whenever I tell people the next big crisis will come from inflation, not deflation, the looks of disgust are worse than when someone says Justin Bieber’s music is not that bad. And when I try to tell them that the true bubble is in fixed income, not stocks, they look at me as if I just slipped the Biebs into the next-up slot on the Spotify playlist.

“Where will the growth come from?” they often ask or, “demographics will keep inflation subdued for another generation,” they retort.

And I must admit, I have always had difficulty articulating how inflation would manifest. Usually, I would go with the classic, “throughout the millennia, governments have always resorted to inflating their way out of debt, and this time will prove no exception.”

But that has always left a sour taste in the mouths of the deflationistas who cannot imagine anything but falling prices and moribund growth. These investors need a theory why the trend will change. And it has always been difficult to slap any research in front of them as the Lacy Hunt deflation crowd seems to have the market cornered with their articulate forecasts that the trends of the last 30 years will continue ad infimum, and that interest rates are going to zero throughout the entire developed world.

Until now…

In a Bank of International Settlements paper from this summer, Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan present a powerful argument that demographics are about to usher in a sea change. I am surprised the paper is not receiving more attention, but I guess with everyone so focused on the supposed coming deflation, this sort of research is not all that popular.

But you should go read the paper titled “Demographics will reverse three multi-decade global trends“ today. I suspect it will be one of the BIS papers of the next decade.

Here is the abstract:

Between the 1980s and the 2000s, the largest ever positive labour supply shock occurred, resulting from demographic trends and from the inclusion of China and eastern Europe into the World Trade Organization. This led to a shift in manufacturing to Asia, especially China; a stagnation in real wages; a collapse in the power of private sector trade unions; increasing inequality within countries, but less inequality between countries; deflationary pressures; and falling interest rates. This shock is now reversing. As the world ages, real interest rates will rise, inflation and wage growth will pick up and inequality will fall. What is the biggest challenge to our thesis? The hardest prior trend to reverse will be that of low interest rates, which have resulted in a huge and persistent debt overhang, apart from some deleveraging in advanced economy banks. Future problems may now intensify as the demographic structure worsens, growth slows, and there is little stomach for major inflation. Are we in a trap where the debt overhang enforces continuing low interest rates, and those low interest rates encourage yet more debt finance? There is no silver bullet, but we recommend policy measures to switch from debt to equity finance.

Higher real rates, inflation and wage growth to pick up, and inequality going down. This is the opposite conclusion that almost all economists are subscribing to. And the paper’s authors are keenly aware of their unorthodox position:

We argue that ageing will lower both desired savings and desired investment, but desired savings will fall by more. The resulting imbalance will require the real interest rate to rise for the market to clear. Just as the real interest rate has fallen since the 1980s thanks to a decline in desired investment borne out of the demographic sweet spot we described above, real interest rates will reverse course along with demographic trends and the resulting changes in savings and investment dynamics.

This is clearly our most controversial proposition, and much of the pushback we receive is based on the argument that demographics will lower potential output growth, and hence real interest rates. We agree wholeheartedly with the first argument regarding output growth. But we disagree that it will also lower real interest rates. Indeed, there is much less reason to believe the two are connected than many believe. We discuss first the path to determining the equilibrium real interest rate and then delve into some of the dynamics that will drive savings lower but keep investment from falling by as much or more.

This paper will not help us decide where inflation and interest rates are headed next week. Nor will it even matter next month. But in the coming years, it will prove unbelievably important. The arguments that deflationistas are using to justify their bullish views on fixed income might the very reasons why you should be short! Take the time to read the paper, file it away, and keep it in the back of your mind when the pundits tell you that bonds have only one way to go - they are right, they have just picked the wrong direction.

Speaking of bonds, often people tell me that investors are not overweight fixed income. Instead they argue the speculation is all in the stock market. I call bullshit on that one.

When we entered the new millennium, US 10-year rates were 5.5%. Since then they have fallen to today’s 2.08% rate. Given the significantly lower rates, it makes sense to believe that investors have shunned fixed income.

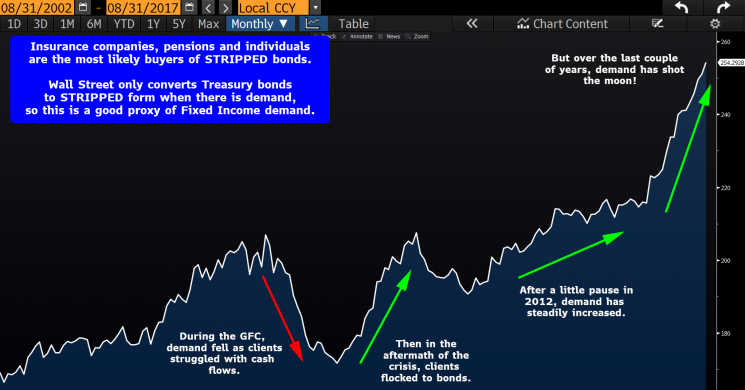

But have a look at this chart of the total amount of US Treasuries held in stripped form.

Wall Street only strips bonds when there is demand for zero coupon instruments. The total amount of stripped bonds gives a good measure of fixed income demand.

In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis, the total amount of stripped bonds fell. That makes sense. Clients throughout the world suddenly found themselves short on capital and extremely scared, so I wouldn’t expect anything else. As quantitative easing was instituted, clients rushed to buy more stripped bonds, and by 2011, the total amount was back to pre-crisis highs (even though rates were significantly lower).

The total amount of stripped bonds went sideways from 2011 and 2012, but then in 2013, they started rising again. But the really amazing action happened in 2016 and 2017. It went parabolic!

The notion that clients are not leaning heavily long fixed income is crap. They are stuffed to the gills as the whole world can only imagine rates and inflation going one way - lower.

Keep this in mind when you are thinking about where the next crisis will come from…

Moving our trading to an even shorter time frame, this weekend I came across this terrific chart from Nordea’s Mikael Sarwe.

Mikael notes that the small open Swedish economy reacts to global economic momentum earlier than the rest of the world. By advancing the Swedish manufacturing PMI a couple of months, we get a sense where European PMI is headed.

In the twitter discussion that followed, m4crotrader had an explanation of why the Swedish economy was such a great indicator.

I have been worried that China’s reflation run is waning, and this Swedish PMI rollover might be another signal. At the very least, I think it might be a sign that the EUR’s run might be getting long in the tooth.

Thanks for reading, Kevin Muir the MacroTourist

Read more by MarketSlant Editor